Technology Adoption Lifecycle

Everett Rogers’s 1962 work Diffusion of Innovations is considered one of the most important marketing concepts of the last century. In it, he described a Technology Adoption Lifecycle that shows how new ideas spread through an environment, following predictable patterns and categories of users.

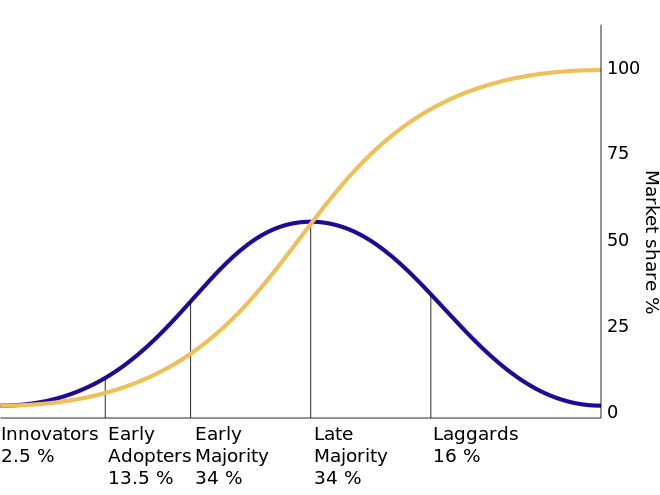

The blue curve itself is a normal distribution of new adopters; things start slow, speed up as the concept takes root, and then slow down as a function of market saturation. The yellow curve is the cumulative distribution of that same curve, showing market penetration of the new idea. Rodgers grouped the distribution into buckets based on standard deviations from the mean, and categorized these into five district groups based on their adoption motivations.

Specifically, the five groups (in order) were:

- Innovators

- Early Adopters

- Early Majority

- Late Majority

- Laggards

Innovators are first on the scene. They are willing to try new productions simply because they are new, and represent roughly 2.5% of the overall population.

Early Adopters are next in line. They are the 13.5% willing to be among the first to try new products, but will only do so if they believe that product solves a problem they have.

The Early Majority is first large bucket at roughly 34% of the total who like the Early Adopters also have a problem to solve, but differ in that they will only try new products if they see other people are using them (social proof).

The Late Majority is the next large bucket at roughly a third, but as opposed to the Early Majority are not seeking specifically to solve a problem but instead adopt because everyone else is already using the product and don’t want to be left out.

Laggards neither have a need nor care about others; they adopt solely because they are forced to as the new product offered is now the only product available, and are the remaining 16% of the market. In this way they share the same characteristics as the first-adopting Innovators, although they themselves are the last-adopting.

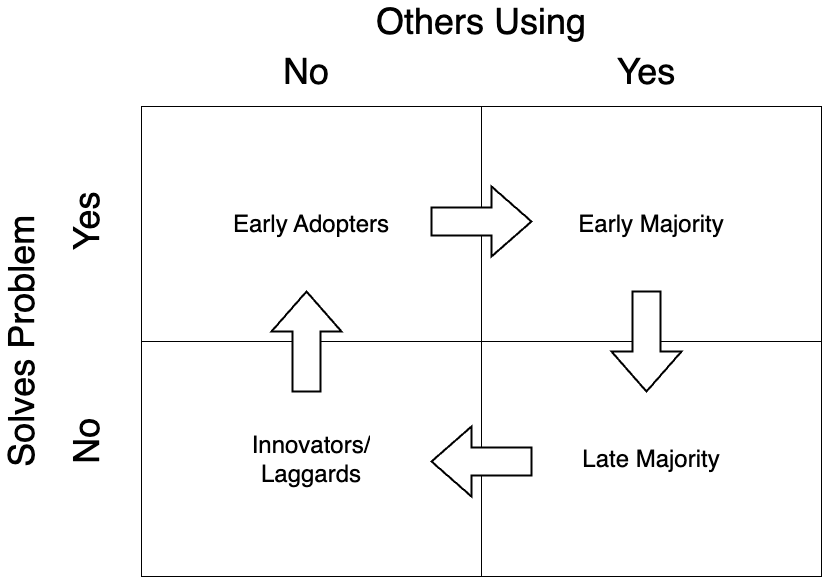

Thus described, we can place the segments in a 2x2 matrix where the horizontal axis describes whether or not a product solves a perceived problem and the vertical axis describes whether others are already using the product. The arrows shows the overall market adoption path.

The Cohorts in Depth

Innovators

The Innovators come for free. They’re always on the lookout for the “Next Big Thing” and are eager to find your new product. Innovators are a great way to shake out initial bugs and defects, but their enthusiasm is not indicative of any greater trend. They the smallest cohort and once the newness of your product dies off they lose interest in favor of the next “Next Big Thing”. Innovators don’t care about whether or not you’re solving a problem and don’t care or even want to see anyone else using it; in fact, being on the bleeding edge is the point. For Innovators, it’s the newness that matters.

Some outbound marketing is of course required at this stage; since there are no users the only way people can find out about the product is if the company tells them about it. However, Innovators are actively seeking out new products at this stage, and so your efforts here should be absolutely minimal. As long as you’re not actively trying to hide your idea, Innovators will find it.

Instead, your goal should be to transition to the next phase, which means that while you are serving Innovators you should be seeking to attract Early Adopters.

Early Adopters

The Early Adopters do have a problem, and are willing to take a risk on products they believe will solve that problem. They don’t care about existing usage; in fact, they are often looking for an advantage over their competitors and so trying something of which others’ aren’t aware is a plus. They don’t specifically care about the newness itself – product characteristics matter a great deal to them. Accordingly, Early Adopters are found when you can demonstrate Problem/Solution Fit.

Problem/Solution Fit refers to the conditions when the product you are offering matches the perceived need of a segment of customers. Note that the “problem” here isn’t always overtly stated; often the customer doesn’t know they have a problem at all, let alone be in a position to articulate it. Rather, finding Problem/Solution fit means that you are conveying a set of product characteristics that attracts the attention of potential customers.

Be aware that often entrepreneurs are themselves “Innovators” in the Rogers sense, and so producing something new is attractive in its own right. Thus it is very often true that the products they create are very exciting to them even though they may never actually fulfill a customer need, latent or otherwise. This is often referred to as “a solution in search of a problem”. However, if a problem never materializes in the customers’ minds then you will never transition into overall market beyond initial Innovators.

Moreover, understand that Problem/Solution Fit represents an expression of intention; whether or not the product actually fulfills the need is secondary at this stage. As such, product availability may be scarce or indeed the product need not exist beyond prototype (if at all.) The main concern is that you’re able to identify a particular unmet need and articulate the solution in a manner that resonates with the Early Adopters.

In this sense, the purpose of the first transition point is to determine whether or not a product should be built at all. Clearly, if you can’t generate any interest then it makes no sense to proceed. And while this may seem self-evident, know that there are countless examples of products built and launched with great fanfare at the cost of millions – and in some cases billons of dollars —- that never achieved any interest beyond mere Innovators.

Perhaps the crispest way to demonstrate Problem/Solution Fit is through Kickstarter or other product-launch platforms. Using these tools an entrepreneur sells the product proposal, sometimes with prototypes or other pre-market product demonstrations. Those which articulate a problem worth solving are able to secure commitments from backers to bring the product to market; if no such demand materializes, the prospective idea (rightfully) dies on the vine.

There are no hard and fast rules when judging Problem/Solution fit. In general whatever interest you see should be sufficient to justify the investment required for the next (or initial) product iteration. However, as a practical matter the first step is binary: meaning, is there any interest at all? The entrepreneur can see the future in ways that others can’t; this is what makes visionary leaps possible. However, if the early adopters don’t share this vision then you should not move forward. Do not look to try and “educate the market” or otherwise bend the customer to your will. Instead, seek actual evidence that demonstrates the customers have a particular desire for your product and a willingness to act upon that desire through the product characteristics themselves.

Assuming you have attracted Early Adopters the next goal is to progress to the Early Majority.

Early Majority

The Early Majority also have problem to solve, but unlike the early adopters they are more risk-averse and aren’t willing to take a chance until they see others using it. They do consider product characteristics, but also must see social proof in order to adopt. This segment is more than twice as large as the first two combined, and represents when a product goes “mass market”. This transition point happens when you demonstrate Product/Market Fit.

Product/Market Fit are the conditions when you fulfill a mass-market need and are starting up the fabled “Hockey Stick” of growth. Going back to our matrix, we see that the new requirement of the Early Majority is seeing the solution in action, demonstrated by the product itself. It’s insufficient to merely be told about the product characteristics; they must actually observe the usage and/or its results.

Thus, the key to attracting the Early Majority is the active usage of Early Adopters. So, while the first transition of Problem/Solution Fit did not require an actual product but merely the promise of one, the transition of Product/Market Fit does mean that a product, however minimal, is in the market. This increases the stakes as we are making more significant investments to enable that production. It also reveals the cause of a common trap that befalls many entrepreneurs: the gap between the early adopters and early majority called “the Chasm”, a term popularized by Geoffrey Moore in his seminal work “Crossing the Chasm”.

To explain, from Rogers we know that Early Adopters will adopt a product if they believe it solves a problem, and we also know that the Early Majority will not adopt unless they see others using it. And so while your product may readily attract early adopters on the promise of a solution, if those users do not produce conspicuous enough usage to attract the attention of the early majority then the bottom falls out of the market and the initiative plummets into the chasm.

This means that your primary objective during the Early Adopter phase is to actually deliver on the value proposition and solve the problem for your customers. It is not enough simply for the Early Adopters to buy your product. They must use your product, and be willing to share their satisfaction with any and all who are willing to listen. If the Early Adopters churn out because you oversold expectations or otherwise don’t fulfill the value proposition, then there is no one for the Early Majority to see using the product, and the chasm gets wider.

The Early Majority transition is particularly perilous because it represents an event-horizon; building a scalable product requires significant resources that can only be justified by significant expansion such as Series A or other growth capital. Up to this point the funding has been Seed, Angel or perhaps even bootstrapped, as the size of the overall market is less than 10%. Investments at this stage are speculative by nature and don’t insist upon immediate growth or profit. Their goal is to provide a future investment opportunity when the firm transitions into larger markets and funding rounds. This provides greater room for the degree of experimentation and trial and error that is typical of startups.

The Early Majority, in contrast, is a mass-market opportunity demanding a funding level to support the expansive growth. If growth materializes, then funding will be plentiful. But if it does not, there may not be another round – or at the very least will be significantly diminished in value. Again, this is why the chasm is so deadly to startups: if they misinterpret early adopter support and raise money before the early majority adopts, their growth stalls and future funding becomes impossible.

Thus, your goal at this stage must be demonstrate that your product actually solves a problem in a way that promotes conspicuous usage. Once this is accomplished, you can ride the hockey stick of growth straight into the Late Majority.

Late Majority

When we reach Late Majority the product has diffused through more than half the population. Here the original problem is now considered solved by your product and is therefore irrelevant as a decision criterion; instead, the main worry for adopters is being left out. For the Late Majority, the only thing that matters is that everyone else is using it. The Late Majority is equal in size to the Early Majority and remains squarely within the realm of mass marketing.

Here, the growth engine is well-operating and has been for some time. The main difference between the Early and Late majority is that the latter, while still growing, is growing at a slower rate (for the calculus geeks, the second derivative has turned negative.)

There is still more than half the market remaining and so growth must be maintained, but at this point a profit model to match the growth model must be clearly established to justify the investments made to date. To be clear, profits themselves may be forestalled in furtherance of a strategic objective. For instance, Amazon is a famous example of a firm that priorities growth above profit whenever possible so as not to stunt the strategic positioning which that growth provides. Still, at some point every business must become profitable, and this final transition represents the prioritization of profit over growth.

This transition is called “Market/Profit Fit”, and it essentially means that you have demonstrated the ability to sufficiently monetize the value created up to this point into the cash necessary to sustain your business. Again, this may seem self-evident, but the most high-profile business disasters when there are colossal sums spent to spur and support growth which never produce a return on that investment. The decision to actually transition to profit-focus is ultimately a strategic one, but every enterprise must have clear evidence of eventual profitability well before entering the late-majority.

That’s because like the transition between early-adopter to early-majority, this transition is permanent: firms that no longer have the opportunity for hyper-growth can no longer secure speculative funding. Any financing must come from free cash flow or sources which demand an immediate return. This is no longer about betting on the future; it’s about harvesting the present. Yes, we continue to grow while in the early majority, but this growth is no longer the leaps and bounds of new market potential, but rather the growth of the overall population, or due to securing market share from competitors. In either case, profit is the final stage and we can no longer tolerate losing money. Lack of performance leads to cost-cutting, layoffs or, in the final analysis, end-of-life for the products or the firm.

Laggards

The Laggards are the final segment who are basically forced to adopt because there is no alternative. They don’t care about solving a problem, but since literally everyone else is already using the product, substitutes are no longer easily available. Laggards care about neither problems nor usage, and so they ironically share the same quadrant as the Innovators.

Laggards are notable not for their characteristics but for what they represent; namely, that there is no “new” left in your new idea. At this point the product is fully diffused into the environment, and it’s time to start considering the next innovation to start the cycle all over again.

This is actually represented by its own transition, called “Idea/Company Fit”. Put simply, it means that the idea proposed for rejuvenating the product line through the next innovation matches the companies strengths, skills, and strategy. Most of the time this consideration is so self-evident that it is never formally considered; still, it’s worth spending at least a short period of time ensuring that the next endeavor is worthwhile at all. Perhaps there is a larger change of strategy or some other in the works that suggest no additional investment in an aging product line. Regardless, take the brief amount of time required to consider the strategic implications of the next innovation – formally or informally – is the best way to close the loop on the technology adoption lifecycle.

Summary

The Rogers Technology Adoption Lifecycle provides a useful set of characteristics for entrepreneurs introducing new products to new markets. The intersection of problem-solving/social-usage at each stage of the Innovators, Early Adopters, Early Majority, Late Majority and Laggards gives critical insight to what the customer priorities are at any given point in time. This in combination with the concepts of Problem/Solution, Product/Market, Market/Profit and Idea/Company fit as the key transition metrics provides the high-level strategic guidance to successfully bring your idea through the entire lifecycle successfully.