The Quest, The Race, The Grind

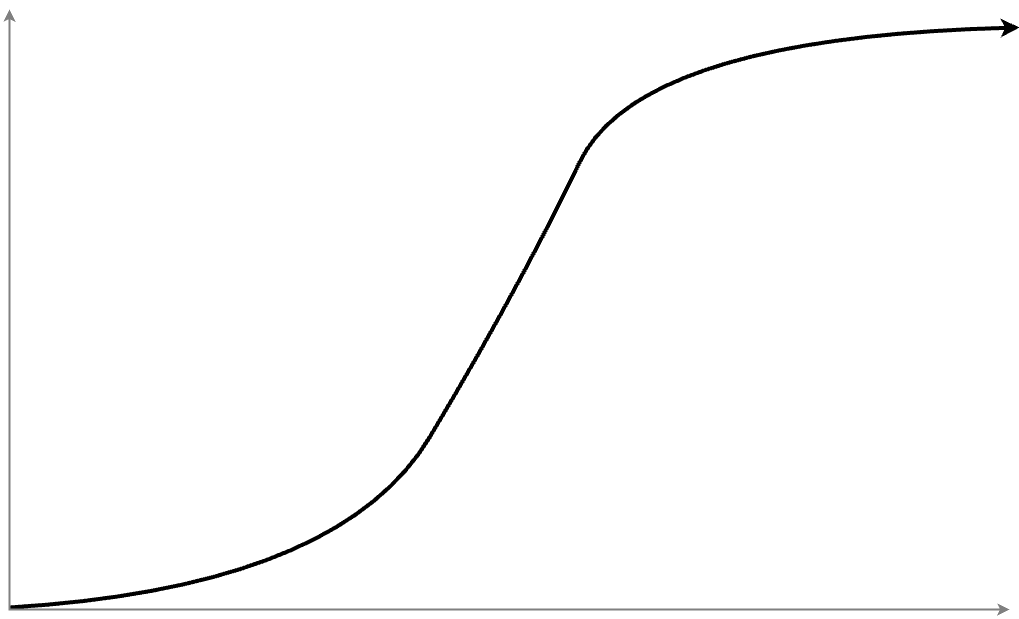

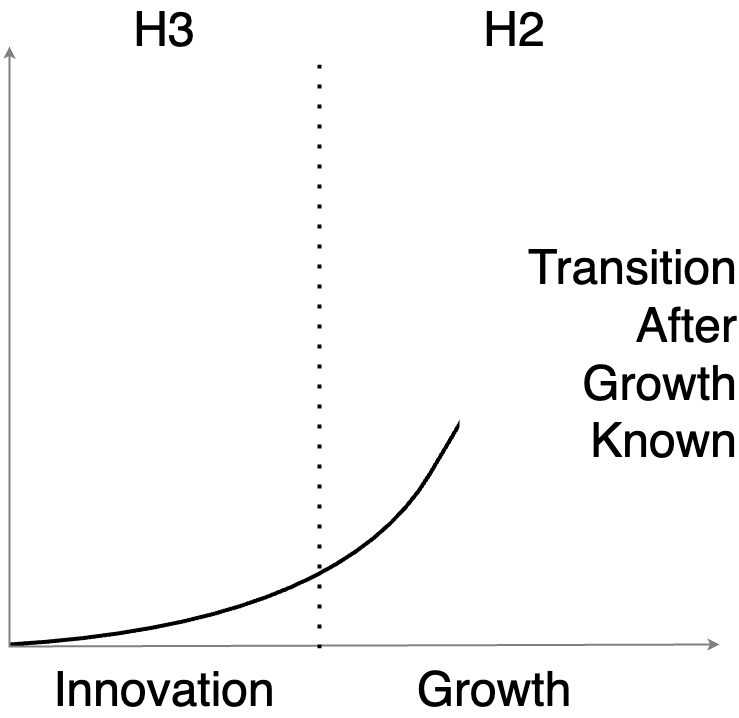

The romanticized version of innovation reads like Athena’s birth–created from an idea in Zeus’s mind, she sprang forth from his head fully formed and ready for battle. Sadly for the entrepreneur, reality never matches mythology. The product lifecycle for discontinuous innovation is neither instant nor straight; instead it follows a logistic path:

This characteristic S-curve is a basic law of nature. It’s not just true of products–it’s true of life in general. Companies start as babies: they keep you up all hours of the night, require constant care and feeding, and produce nothing but shit for years. If they survive to adolescence, they start to grow amazingly fast, consume huge resources in food and education, and are clumsy and awkward as they figure out their place in the world. Finally, at maturity and after huge investments of time and money, they reach adulthood and find a productive role in society that justifies the effort required to get them there.

Life never follows a linear path, and neither does your product.

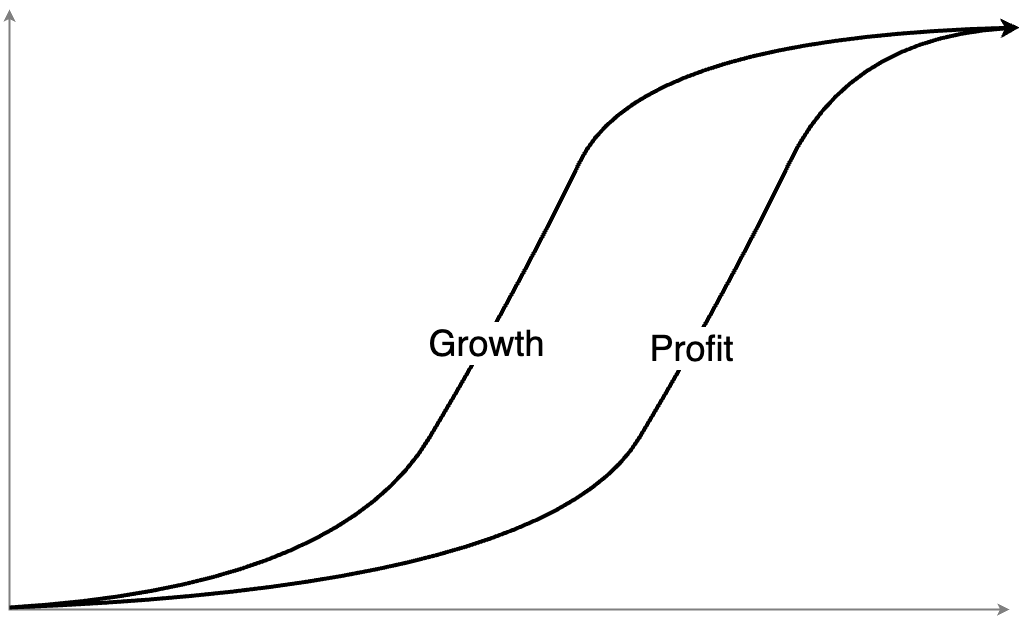

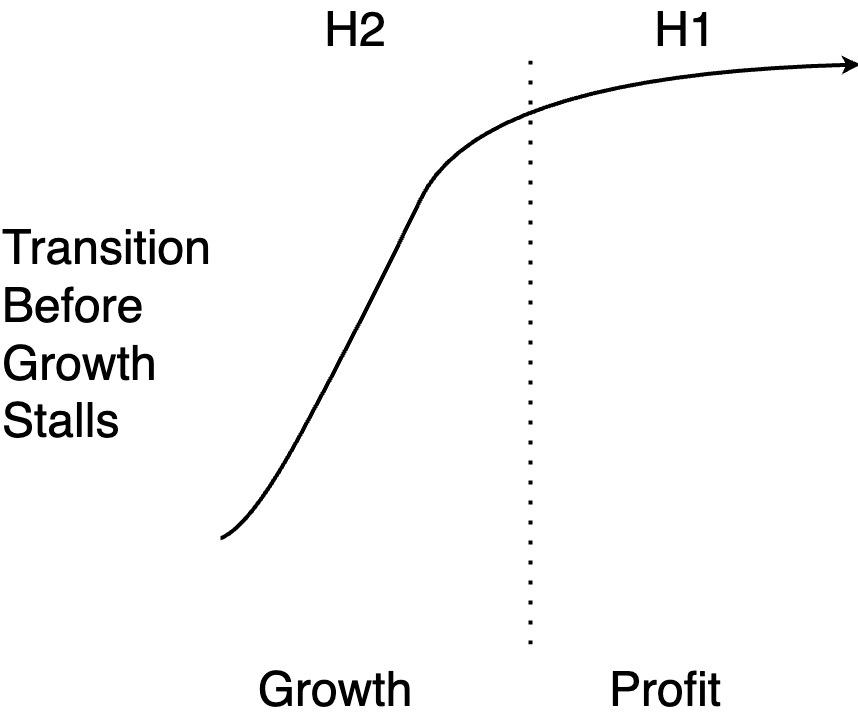

The Three Horizons model, developed by McKinsey and Company and articulated in “The Alchemy of Growth” in 1999, segments this S-curve into three distinct phases. First, there is the innovation phase; the long, flat portion where the idea is formulated and the initial versions of the product are created. Second, there is the non-linear growth phase; this is the fabled ‘hockey stick’ of rapid adoption. Finally, we have the profit phase where the rate of growth stabilizes, and the project reliably returns cash. To emphasize the target state of profitability, McKinsey used a “countdown” approach, and so the horizons progress 3–2–1: meaning, Innovation is Horizon Three, Growth Horizon Two, and Profit Horizon One, which we’ll shorthand as H3, H2, and H1 respectively. (Note that this numbering scheme is counter-intuitive as most tend to think that products progress through phases as 1-2-3; be careful when discussing horizons as it’s easy to get confused.)

McKinsey articulated the horizons to demonstrate the importance of a balanced product portfolio. H1 projects represent current profits, but they don’t last forever: if there aren’t H2 projects already growing to replace H1 when it reaches end-of-life the firm is in jeopardy of having no profits. Similarly, there must be initiatives in H3 ready to replace H2, which themselves replace H1. McKinsey’s point was that failure to have projects simultaneously in all three horizons puts the firm at risk of disruption.

In this article, I’m going to use the same horizons but for a different purpose. I’ll start by defining the horizons themselves. Next, I’ll outline how each stage’s degree of certainty dictates a particular management approach. Third, I’ll specify the transition conditions necessary when moving stage to stage. Finally, I’ll show how this all leads to a specific financial model for innovation that differs sharply from convention. With that overview, let’s get started.

The Horizons Defined

We start with Horizon Three: the innovation phase prior to either profit or growth. Progress should be measured by the optionality new growth opportunities provide the firm. H3 projects are run by entrepreneurs who can realize the potential of new ideas. Systems are in constant flux adjusting to market conditions, if they exist at all. Innovation projects occupy the smallest amount of the firm’s time and attention, generally about 10% total. It’s the Quest for the next big thing.

Horizon Two is about non-linear growth. Here progress is measured by top-line metrics like revenue, unit sales, and market share. H2 products readily sacrifice immediate profitability for larger and more defensible profits in the future. These projects are run by leaders who scale – in marketing, distribution, partnerships, and so on. This kind of ‘hockey-stick’ growth is chaotic; the systems are constantly playing catch-up and tend to be fragile and inefficient. H2 products generally demand about 20% of a firm’s resource. They are exciting and trendy, and since they are exciting and trendy they attract attention from competition – thus the Race is on.

Horizon One produces predictable profits. This is the ultimate destination for any business. The focus is on bottom-line metrics like net income, return on invested capital, and profit margins. H1 projects are run by managers who focus on optimization, stability, efficiency, forecasting – all the things that keeps a business running smoothly. Growth still happens, but it’s incremental growth in service of maintaining profitability – never at the expense of it. H1 systems are stable, robust, well-maintained and well-understood. These are the products most associated with a firm’s brand, and demand about 70% of a firm’s time, attention, and resources. It’s the Grind of day-to-day business.

The Horizons and Certainty

From the above, we can properly recognize each horizon by its two components: growth (by which I mean non-linear growth, not incremental) and profit. More specifically, it’s the degree of certainty of both growth and profit that defines where a particular product lies. Consider the following matrix.

| H3 | H2 | H1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Certainty | Growth | Profit | |

| Low Certainty | Growth | Profit |

With an H1 business we have solid knowledge of growth and profit and can make confident predictions about future behavior. We rely on the dependencies in the value chain to work in a certain way – suppliers, customers, operations, support, competitors – and focus on tuning our systems for maximum efficiency. And while we are always adjusting to changing market conditions, by and large we know everything we need to know to operate our business successfully.

With H2 businesses we have rapid growth and invest heavily in scaling our operations and marketing accordingly to keep ahead of the curve. We must assume that we’ll profit in the future or the growth spending is pointless, but until that happens it must remain an uncertain assumption. Thus, in H2 we have a mix of certainty: high on the growth (because it is happening), low on the profit (because it isn’t happening).

Finally, with H3 business we only know that we’re building something that costs money. To be sure, great effort is expended determining what to build and how to take it to market. Still, until realized both growth and profit remain as assumptions. Thus, H3 is low certainty on both growth and profit.

The product lifecycle is therefore properly characterized as the development of a growth engine, followed by its corresponding profit engine. Ultimately our goal is to get both systems running at scale, which can only occur as we gain certainty of how each engine operates.

This is important because management approaches differ depending on the degree of certainty. High certainty means Execution–we know what the job is and how to do it, so let’s get it done. This is the time for scale, specialization, and systemization. We have our engines running, and the primary obligation is to keep them running smoothly.

In contrast, low certainty means Exploration–we need to validate our assumptions before scaling into the unknown. This is the time for tests, flexibility and agility; our main task is to learn from the market as rapidly as possible. This is an iterative, non-linear process that is more focused on turning our assumptions into knowledge (ie, building certainty.)

| H3 | H2 | H1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Execute | Growth | Profit | |

| Explore | Growth | Profit |

Overlaying the tactics on the horizons, we see each stage has its own unique mix of approaches. H1 is solely about execution; we’ve established our growth and profit engines and the focus is on optimizing each. H2 requires a hybrid approach: we need to execute effectively to keep the growth engine humming while simultaneously exploring the profit engine to follow (the only stage with such a dual-focus). Finally, H3 is pure exploration; we need to validate the assumptions on which we’re counting to produce non-linear growth.

The Horizon Transitions

Since the horizons demand management approaches that are mutually exclusive, it implies that there are two points of transition where we move from exploration to execution on each engine.

The transition from H2 to H1 is defined by the relationship between the growth and profit engines. Remember that projects in H2 have dual-goals: they must maintain their growth engine as they test their profit engine. When calling H2 “the Race” I mean more than just against the competition. The critical race is actually between the dual goals; meaning, you must find a reliable profit engine before your growth stalls. As long as you continue to experience non-linear growth, you will find investors willing to fund that growth. However, as soon as growth stalls everyone is going to start asking questions about the profit that was promised. You win the Race when you successfully transition to H1 before your growth stalls.

The transition from H3 to H2 is defined by a discrete event: growth financing. Growth is expensive – production needs to scale systems, marketing campaigns need to be run, managers need to oversee everything – which rarely can be achieved through internal cash flow. And since growth financing’s purpose is to (spoiler alert) produce growth, growth must follow or the project will not get subsequent financing. Thus, the transition should occur (ie, you should take growth financing) only after growth is known.

The transitions are critical because the product lifecycle has another built-in natural law: it is one-way. Just as you can’t go from adulthood back to adolescence or childhood, once you enter into a new horizon you can’t go back to a previous one.

When you’ve reached the H1 profit phase those profits need to continue, full stop. There are countless employees, vendors, distributors, etc. all dependent on the cash provided by the profit engine, and so turning suddenly into a money-losing operation is not feasible. Similarly, once in H2 you need to grow. Growth requires significant cash to finance the expansion, and that investment must deliver on its promise for current growth. If growth stalls before the profit engine kicks in, funding dries up and with no other cash available the entire project collapses. Once traversed, the two transition points are permanent.

Innovation is an Option

From this we can see that H3 provides innovators with leverage not present in the other horizons; namely, they can choose when to start the Race. Initiatives that receive growth financing from the outset effectively skip H3 entirely and proceed immediately to H2, starting the Race. However, if innovators instead raise small amounts they keep expectations consistent with their exploratory mission. Accordingly, H3 innovators should raise as little as necessary, not as much as possible. Keeping H3 funding small gives the innovator the opportunity to learn more about those assumptions’ veracity before committing to a larger-scale growth investment. This perfectly describes an existing financing instrument known as options.

Options are the right, but not the obligation, to make a transaction in the future at a price set in the present. They delay investment decisions until more is known about the market, reducing risk when facing uncertainty. An option’s value comes from the ability to decide itself, rather than from the results of the decision. So unlike H2 investments which must produce growth to be valuable, H3 investments must simply provide options for future action. These investments are a fraction of equivalent H2 investments and have value even if the eventual decision is to not enter the Race because the certainty of winning is too low. In this very real way, Innovation is an Option.

Pointedly, most corporate innovation does not follow the option model. Instead, growth funding is approved based on the assessed quality of the assumptions (i.e. the quality of the pitch) and subsequent progress measured on how closely the budget and schedule hew to said plan. This isn’t altogether surprising; larger firms are dominated by products that are in H1 and have been for some time – often so long that there is no one who remembers anything different. It is, and always has been, about relentless execution, and the same type of careful planning that defines the core products gets applied to new ones. So it is that market size is divined, sales are projected, development is outlined – an entire business plan is concocted that, once approved, defines the path to success.

So rather than validate the simplest assumptions, more complex ones are created that – due to their complexity – provide a false sense of security. Still, no matter how much we camouflage them as knowledge, assumptions stubbornly remain so until tested against reality. And when that reality eventually happens if the outcome is different than expected then culpability inevitably falls not with the plan (the boss approved it after all) but in a “failure of execution”.

Corporate innovation should reject this anti-pattern and instead respect the growth and profit engine exploration phases for what they are: the opportunity to test our assumptions against reality, with the implicit acknowledgement that the answer might be “no, this assumption is incorrect”. Employing an option-based model for H3 innovation aligns the funding mechanism to the desired outcome, and provides all the necessary tools (valuation, risk-measurement, metrics, etc.) to support corporate governance.

Obviously not all products make it to H1. However, those that do must at some point prove their assumptions. The path to H1 is, in effect, the process of exploration, increasing certainty until we achieve the knowledge necessary to support scale. By accepting this and valuing our exploratory efforts in terms of the optionality they provide the firm, we can focus more on what’s real and reserve Athena for myth.